Golden Kanazawa

Jane Johnston

Gold: Kanazawa truly glistens with it. All of Japan’s gold leaf is currently manufactured there, so it’s no surprise that there’s gold on all manner of things in this city on the western coast of Honshu.

My partner, Kerry and I went there to find and find out about gold leaf, a search leading us to one of the world’s few museums to focus on gold leaf, and to first-hand experience of traditional gold leaf making with a master craftsman at HAKUZA Inc., a leader in the manufacture and application of metal leaf.

Hakuichi Co. Ltd. store, Kanazawa (Higashiyama). Photos: Jane Johnston

But what better to start with than ‘gold leaf ice-cream’, iconic in Kanazawa. Directly in front of us, at a store of the gold manufacturer Hakuichi Co., Ltd., staff pick up a gold leaf with bamboo tongs and bring it, shimmering through the air to a cone of soft serve and expertly wrap it around the top. The cold gold beads with tiny drops of condensation, adding sparkle to an already spectacular sight.

Gold is undetectable by taste; what you buy is delicious ice-cream and a feast for the eye, with the idea of eating gold – a rare metal imbued with rich meaning in Japan and around the world.

The (Kanazawa and Tokyo) stores of Kanazawa’s several gold manufacturers offer a trove of gleaming goods. We see jewellery, clothing, beauty products, homewares and more to eat as well as some to drink – tea with fragments of gold leaf, anyone?

HAKUZA Inc. bracelets and snake figurine in porcelain and gold leaf. Photos: Jane Johnston. Exterior wall of HAKUZA Inc. in Kanazawa (Hikari-gura) – pure gold platinum leaf and gold leaf with plasterwork. Photo courtesy of HAKUZA Inc.

But there’s much more to see than these shops, and in Kanazawa’s temples and other historic sites, antique shops, and many museums of interest, there are exquisite applications of gold leaf to discover. As you explore, it’s soon evident that the city has a rich heritage of several crafts, gold leaf and more – dyed silks, ceramics, and works of metal in metal inlay called Kaga Zogan, to note just a few.

This heritage originates from the Maeda family’s rule of the Kaga Domain from 1583 until the end of the Edo period with the 1868 Meiji Restoration, when the Tokugawa shogunate was abolished. The domain was prosperous and generations of the Maedas used their wealth to encourage various crafts to flourish in the domain’s castle town of Kanazawa.

Garden and nest of mid-Edo period boxes at the Nomura-ke Samurai Residence, Kanazawa. Photos: Jane Johnston

Craftsmanship is still very much alive in Kanazawa today, something that makes Kanazawa exciting to visit and is formally recognised by UNESCO’s designation (since 2009) of Kanazawa as a City of Crafts and Folk Art in its Creative Cities Network, currently one of just 66 globally.

Kanazawan gold leaf making is said to have been initiated during the 1583–1599 rule of the first Maeda lord, Toshiie. All leaf used to be made by the traditional entsuke method which creates the thinnest gold leaf in the world: just 0.0001 millimetre (0.1 micron), so the leaf is incredibly supple and weighs only about 0.025 of a gram over a typical leaf, a square eleven by eleven centimetres.

Immersive walk-in installation of gold leaf in the Tokyo (Nihonbashi) store of HAKUZA Inc. Photos: Jane Johnston.

The entsuke method is unique to Japan, and UNESCO inscribed it as world Intangible Cultural Heritage within its 2020 listing titled ‘Traditional skills, techniques and knowledge for the conservation and transmission of wooden architecture in Japan’.

In Kanazawa today, gold leaf (kinpaku) is still crafted using the entsuke method, but much more is mass produced using a method called tachikiri that was developed in the late 1960s.

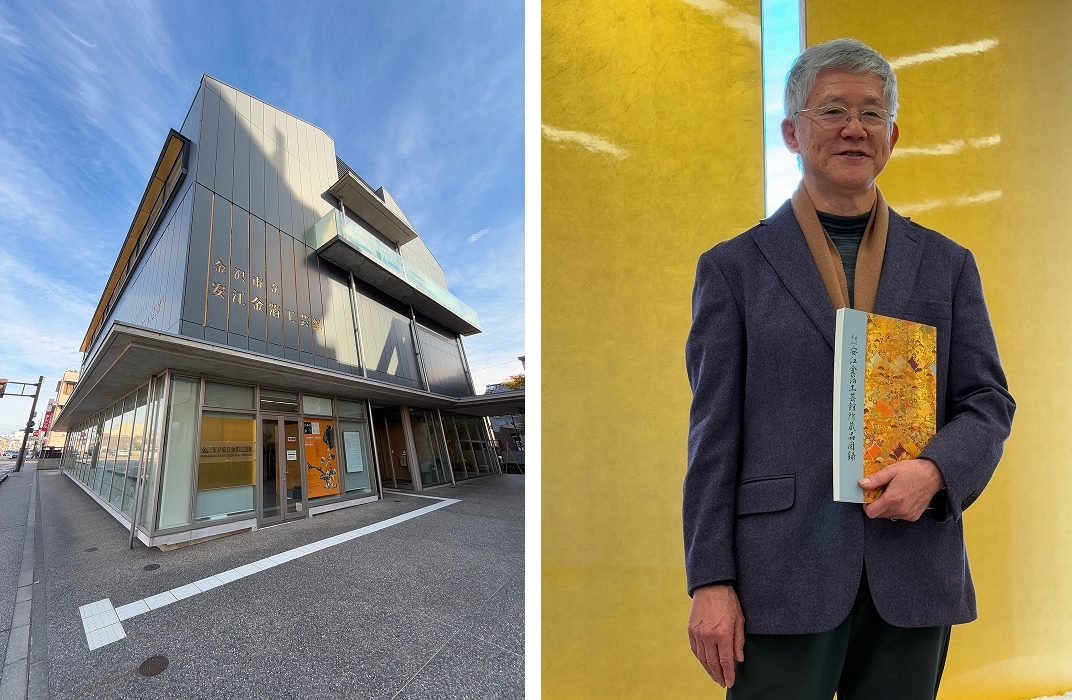

Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum and the Director, Mr Akitaka Kawakami. Photos: Jane Johnston

At The Museum

At the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Museum, we were honoured to meet the Director, Mr Kawakami Akitaka. He begins to show us around, saying, ‘This museum was founded around fifty years ago by Yasue Takaaki, a gold leaf craftsman. Around ten years later, he donated it to the city, who later moved it to this new building.’

In a large space where the display changes seasonally, we see a spectacle of contemporary metalworks, mostly on loan. More usually, this space shows selections from the Museum’s rich collection of historic and contemporary items of ceramics, maki-e (decorative lacquerware), metalworks, glassware, textiles, screens, calligraphy and more.

Museum displays: TAKAHASHI Kaishu, 20th century, ‘Album of Gold and Silver’, ornamental vase in bronze with gold and silver inlay; metalworks exhibition photographed Nov 2024. Photos: Jane Johnston.

Other areas of the Museum shed light on the nature, history and production of gold leaf, and we focus in on how gold leaf is produced.

Zumiya craftsmen start, forming ingots from gold melted with small amounts of silver and copper to make an alloy (still called gold) and then machine-rolling them into belt-like strips. Next, they repeatedly cut and beat the gold, to eventually produce zumi – twenty-by-twenty-centimetre squares of gold, around 0.001 millimetre (1 micron) thick.

It’s hakuya craftsmen who undertake the next stages of cutting and beating, transforming the zumi into finished leaves called haku which are then trimmed into neat squares of the desired size and packaged, ready for sale.

Museum displays: beating machines; fine strips of gold leaf, wound with silk to make gold thread. Photos: Jane Johnston

In all of this, the key action is beating squares of gold, stacked one on top of the other, while inter-leaved by squares of paper. In the entsuke method, the gold-beating paper (haku-uchi gami) used by hakuya is a type of Japanese handmade paper (washi) made from Gampi bush bark. Hakuya must treat the raw Gampi paper (Gampi-shi), to make it suitable for use in gold beating.

Mr Kawakami gives a sample of already prepared paper and emphasises its indispensability, saying, ‘The paper is the most important thing of all for making gold leaf’. Its ultra-smooth surface and robust nature are what enable hakuya craftsmen to beat the malleable gold into such thin, well-formed leaves.

Picture this: the gold thins in response to the vertical force applied by beating, and so it expands horizontally. Because there’s no appreciable friction between the gold and the paper, the gold can expand gradually and evenly in every horizontal direction, maintaining a square shape.

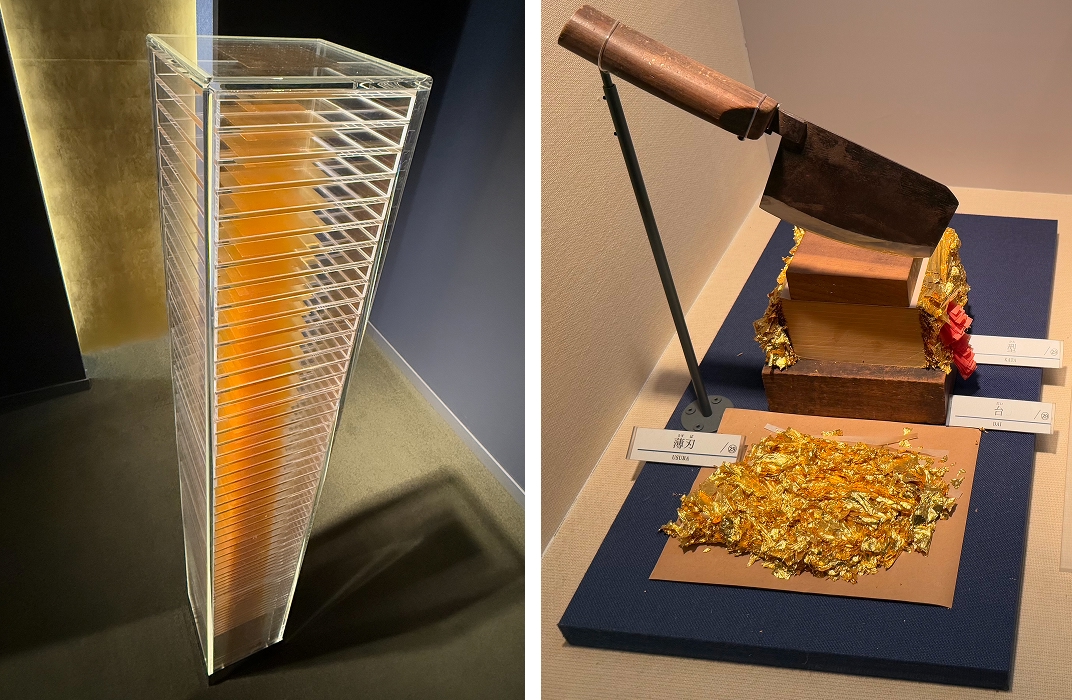

Museum displays: one hundred leaves stacked into Perspex to showcase the translucency of gold leaf; final leaf-cutting step in the tachikiri method. Photos: Jane Johnston.

Originally, hakuya craftsmen used hand-held hammers. In the early twentieth century, beating machines were invented to help with gold beating and with preparing the gold-beating paper. Essentially, they are automated hammers with a metal pole that repeatedly rises and strikes down with great force and speed, and Mr Kawakami shows us some (static) examples on display.

The late 1960s development of the tachikiri method enabled mass production. In this method, gold is machine-beaten between sheets of industrially produced glassine, coated with carbon on both sides. The final step in which a stack of interleaved paper and gold is sliced to size, all at once, is what gives the method its name – tachikiri means ‘cut’.

Contrast that with leaves of final thinness being trimmed one-by-one in the entsuke method, to instantly appreciate that the tachikiri method is oh-so quicker.

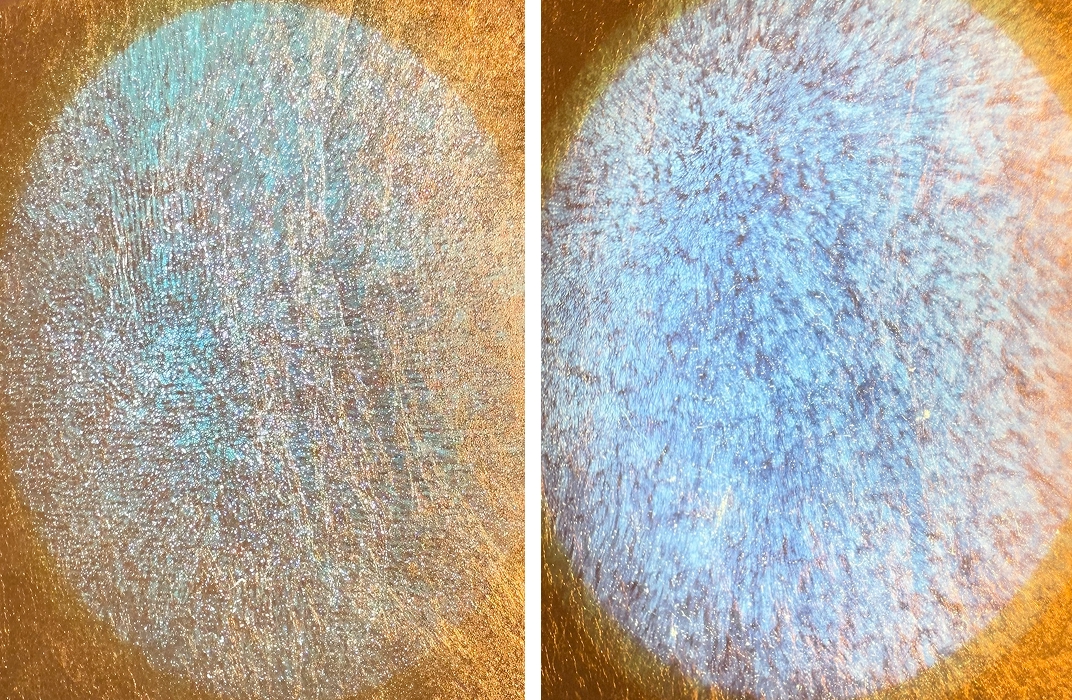

Museum displays (detail view): back-lit gold leaves, entsuke (left), tachikiri (right). Photos: Jane Johnston.

Mr Kawakami says that ‘modern gold leaf’ made by the tachikiri method makes up over eighty percent of Kanazawa’s current total leaf production, and that it looks different to entsuke-made leaf, at least to an experienced ‘eye’. The two methods impart different textures to the leaf surface, creating subtle differences in how light reflects.

Gold leaf is translucent, and Mr Kawakami shows us a display of two back-lit leaves that allows us to compare the textures. We see a tight grid-like patterning on the entsuke-made leaf, pressed into it by the grain of the gold-beating paper, while the tachikiri-made leaf is more sparsely and randomly patterned.

Mr Kawakami says, ‘They say modern gold leaf is more brilliant, glossy, while traditional leaf has a softer, more modest lustre.’ Only the more laborious and expensive entsuke method can produce leaf that closely resembles historic gold leaf; entsuke-made leaf is more suitable for the restoration of heritage objects and buildings, with care to use an appropriate alloy ratio – this ratio of gold vs silver vs copper determines the hue of the leaf.

Mr Hisaki Haseda and Kerry at the HAKUZA Inc. main store, Kanazawa (Moriyama). Photos: Jane Johnston

With a Master Craftsman

Now it’s time to get practical. Arriving at the main store of HAKUZA Inc. for a Gold Leaf Experience Master Plan program, we’re privileged to meet Mr Haseda Hisaki, who works on sales and public programs, and Master Aoshima Shigeo, a hakuya craftsman and one of only around twenty entsuke craftsmen in Kanazawa today. They talk with us about the craft of gold leaf and demonstrate and then guide us with care and good humour as we try some entsuke processes.

The title ‘Master’ signifies years of training and experience, and more than fifty in Master Aoshima’s case. Kerry and I had no hope of performing his craft at anywhere near his level of skill. We categorically proved that and deeply appreciated the breadth of his skills, not least physical composure.

A laugh, a sneeze, a gesture, even a subtle one, can tear a leaf that’s nearby, out in the open, or send it fluttering away from where you want it to be…

Rarely are the waves of air pressure which we all create around us when we move so dramatically apparent as when around material as ultra-light and eye-catching as thin sheets of gold.

Master Aoshima in a mid-method task of moving gold leaf. Photos: Jane Johnston

Master Aoshima embodies calm. He moves deftly, precisely, and without making any waves that might sabotage his work. On the contrary, he chooses moments to usefully create them with gestures that look magic.

For example, in a mid-method task where bamboo pincers (take-bashi) are used to transfer squares of gold from a beaten packet of gold and gold-beating paper, into a ledger – a book with pages of another type of washi. Once the gold lands from the air onto a page, it sits somewhat loosely on the page, rumpled like a sheet on an unmade bed, even for Master Aoshima who shows us the remedy...

Holding a hand open over the gold, palm down, he swings his fingers down. The gold instantly ripples and shimmers under his hand before eventually resting still and almost perfectly flat on the page.

The Master never touches the gold directly. If he did, the forces of static electricity would play havoc with his work. He only touches it with long instruments made of materials such as bamboo which are poor conductors of electricity.

Master Aoshima and Mr Haseda assist Kerry with the same mid-method task. Photos: Jane Johnston

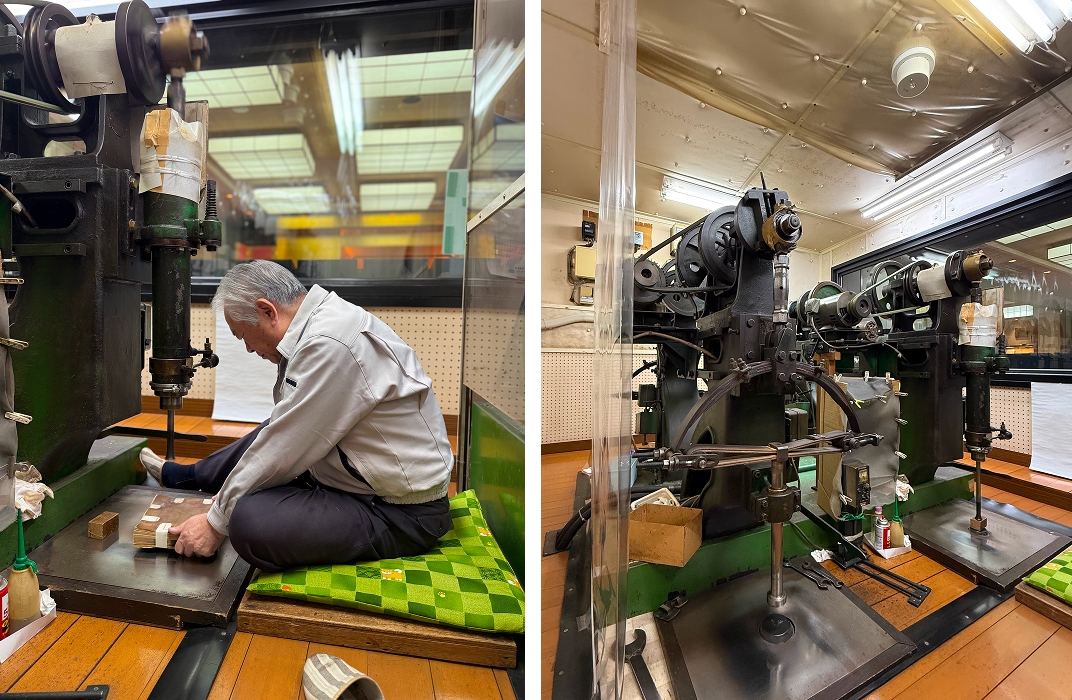

And as we watch Master Aoshima beat the gold, our respect for him and his equipment increases. He takes up a bundle of squares of gold (typically 1800), interleaved with squares of gold beating paper (sized eighteen by eighteen centimetres), covered top and bottom by cow leather.

Seated at the machine (haku-uchi ki), he moves this bundle small distances back and forth, side to side, with great control while a metal pole automatically slams down onto it with a tonne of force, 700 times per minute. The machine makes a fast and (pleasantly) memorable clatter, and Master Aoshima’s face shows intense concentration.

Briefly at the machine ourselves, we simply hold the bundle in place, feeling the power of the machine, and I imagine the edges of the thinning gold advancing towards the edges of the paper.

Master Aoshima at the haku-uchi ki gold-beating machine (left) and beating machines (right). Photos: Jane Johnston

This ultra-smooth gold-beating paper really is crucial; Mr Haseda calls its preparation ‘the most important work for craftsmen’. We experience one task in which forty sheets of part-prepared Gampi-shi are arranged into a vertical stack with a specific many-pointed (petalled) shape. Seen from above, it resembles a chrysanthemum flower.

Mr Haseda explains that the masters pile up many ‘chrysanthemums’ and soak them in a liquid lye made from the ashes of burnt rice straw, mixed with persimmon juice for tannins that discourage mould, bacteria and insects, and with egg whites that help to smooth the paper. During this soaking, the chrysanthemum-patterning allows the liquid to penetrate evenly through every sheet.

The Master forms beautiful ‘chrysanthemums’, seemingly in no time. Let’s just say that Kerry and I were less proficient, and as we talk and perform the tast, Kerry and I gain a sense of the vast time that hakuya masters spend on the various repetitive manual tasks that transform the Gampi-shi. In fact, they spend more time on these, than on working the gold.

Mr Haseda adds that paper preparation takes more than half a year, from start to finish, emphasising that various steps can’t be hurried, including natural air-drying of the paper in humid Kanazawa.

Zumi being inserted into a packet of gold-beating paper using take-bashi, and Master Aoshima with the ‘chrysanthemums’ made during paper preparation. Photos: Jane Johnston

In the last entsuke tasks, squares of gold at their ultimate thinness are individually trimmed to size and stacked.

Each gleaming square is moved from a ledger of washi to a pad of deer leather (kawaban), and lightly pressed with a square bamboo cutting frame (takewaku). A perfectly square haku results, and after the excess gold around its edges is pulled aside, it’s moved one last time and laid across a square of washi made of Mitsumata tree fibre. Once the pile rises to one hundred haku, interleaved with washi, it’s bundled ready for sale.

Mr Haseda and myself in the last entsuke method tasks. Photos: Jane Johnston and Kerry

The washi is larger than the haku and, as we try these tasks, we see the ‘border’ of paper around the gold in these bundles that gives the method its name – entsuke means ‘bordered’.

And with the gold at its utmost and mind-bendingly fragile thinness of 0.0001 millimetre (0.1 micron), we find that these last tasks are far harder than they sound…

We tear and gash some gold but, still, are successful for beginners. Mr Haseda puts the challenge that we’ve felt throughout the program into perspective, saying, ‘It is said that it takes ten years to master the skills. It’s a combination of technique and intuition, developed over a master’s accumulated experiences.’

Kinkaku-ji Temple in Kyoto, also called the Golden Pavilion. Photos: Jane Johnston

Talking about the use of entsuke-made leaf in heritage work, Mr Haseda mentions historic sites including Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto, a temple also called the Golden Pavilion. HAKUZA is one of the companies that have provided leaf for its restoration.

Kerry and I had visited the Pavilion just days before and marvelled at it. It’s an iconic site for Japanese gold leaf, with some 200 000 leaves entirely covering its exterior top two floors and interior top floor.

Now that we can better appreciate the enormity of meticulous entsuke craftsmanship that’s on view there, our memories of the Pavilion (and other kinpaku across Japan) feel more lustrous.

After, walking back to our hotel, we can’t take our eyes off trees in their stunning autumn gold. It’s impossible to avoid seeing gold everywhere in Kanazawa, and why would you want to?

Detail view of the gold leaf tearoom at the HAKUZA Inc. main Kanazawa (Moriyama) store, and Autumn sunset in Kanazawa by the Asano River. Photos: Jane Johnston